Seventy-four years ago, as British rule finally ended in India in the summer of 1947, the country was split into two nations, India and Pakistan – a historical event known as the partition.

The unprecedented violence, loss, and death that ensued, mainly along religious lines between Hindus and Muslims, haunts the subcontinent to this day. Anywhere from 10 to 20 million people are thought to have been displaced in the aftermath, with up to two million people dead.

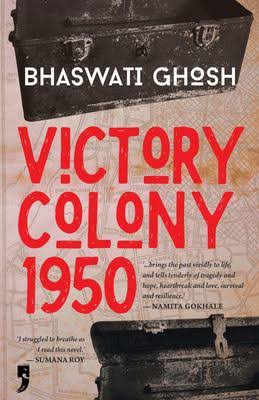

Victory Colony, 1950 is the debut novel by Ontario-based writer Bhaswati Ghosh, which tells the story of Amala and Kartik, two siblings who are living in the wake of this dramatic change and forced to escape after their parents are killed in a massacre in their East Bengali town. Hungry, tired, and terrified, the siblings arrive in Calcutta, a city already struggling to cope with the massive influx of East Bengalis escaping the violence.

Shortly after their arrival in Calcutta, Amala is found by Manas, a volunteer working at one of the refugee camps being set up in the city. There, Amala must face her new reality as a displaced person and learn to live with the trauma caused by the loss of her parents, and her ancestral land.

Despite being two young people from vastly different backgrounds – Manas, a university student from the upper class, and Amala, a village girl from the lower class – find common ground. Together with a group of refugees from the camp, they later help build Bijoy Nagar, which translates into the Victory Colony of the title.

A novel steeped in history and a deep sense of place, Victory Colony, 1950 is a story about resilience and self-empowerment, two qualities needed for survival when faced with unspeakable tragedy. but also ultimately about the East Bengali refugees’ inexhaustible generosity, solidarity, and dignity. What’s more, reading Ghosh’s novel in August 2021 as another cruel humanitarian disaster unfolds in Afghanistan, was a strong reminder of the need for stories that bring the focus back to the individual human beings caught in the maelstrom of history.

New Canadian Media recently spoke with Ghosh about her debut novel, the history behind the fiction, and the importance of telling the stories of people usually forgotten by history. The following is a condensed version of the conversation.

Your writing moves between nonfiction and fiction, but mainly nonfiction. Why did this story have to be told via fiction?

That’s a great question. There is a lot of nonfiction, the documented history, on the partition of India that exists. There is not a lot of fiction from the eastern part of India’s partition. So, you probably know that when India was divided in 1947, it was along two borders, the western border, which is the state of Punjab, and then it was on the eastern border, which was the state of Bengal. So, the so-called partition literature — the fiction — comes from the western part. That is the Punjab side. There is not a lot of fiction, almost none, in English at least, that comes from the east. But that was not the driving force behind my decision to write a fictional story. More than 70 years have passed, there is a lot of time that has already elapsed. And I’m not a historian. I’m not an academic person. That is not my area. But I am a writer. And while I have focused heavily on nonfiction, I also write fiction. So, there was an opportunity that presented itself to me from a new publishing house that was coming up. And this was the story at that point in time that I wanted to write.

Why do you think the fiction has focused on the western border rather than the eastern border?

There are a few reasons, but I think the most distinctive reason for that is the nature of the partition that took place along the two borders. The partition on the Punjab side was extremely violent. There was a lot of bloodshed and there were widespread communal riots between communities. And along with that, there was massive loss of property because people were just being displaced. So, it was a really horrific kind of event that unfolded on the western side. In the east, there was not that much violence and bloodshed. It was a lot quieter and mainly evolved in terms of displacement. This meant that you lost your land, your belongings, you were now refugees.

Also, the demographics of it were very different. On the eastern side, a lot of middle-class and upper-middle-class people were already working in the Indian part of Bengal. They were already there, and they had connections. My grandfather was one of those people who came from the east. He had a job in West Bengal, in Calcutta. So, when the division happened, it wasn’t difficult for them to move over. It wasn’t that much of a painful and extremely traumatic experience. It was for the permanence of the division – the pain was there. But in the short term, at least in the immediate aftermath, making the switch was not that difficult for them.

So, I guess that is how it also reflects in literature and even in the films that come from that side, you will see there’s a big body of lyrical films which talk about the pain of separation from your land and your known universe, but you don’t see a lot of the physical trauma or the carnage and bloodshed that you see in the stories from the west. So, I think that’s probably the main reason why there is a lack.

Your book, however, does describe some of the violence that takes place on the eastern border.

Yes, [the violence] did happen, but it did not happen right at the time of partition like it did on the west side. While many people already had connections in Calcutta because they were educated, the poor people, the poorest of the poor, they remained. They had no choice. And it was only a couple of years down the line, in 1949 and 1950, that riots broke out.

So, my story takes root from that kind of an incident, where now the poor have absolutely no choice, they cannot continue to live there because their lives are threatened. But when they come to the other side of the border, they are not welcome because they are not bringing a lot with themselves. And it’s a complex situation because now India also has to deal with this huge influx of refugees.

Another thread of this, which is also mentioned in the book, is there was an expectation that the refugees who came from the east would return once all that violence died down and normalcy returned. So, there was no rehabilitation program in place from the government, which was the polar opposite of what happened for the Punjabi refugees.

Historical novels tend to be large in scope or filled, at least in part, with historical figures that loom large. Victory Colony, 1950, despite being set in this sort of monumental event in the history of the country feels very intimate. Was this a conscious decision, to keep the narrative close to the refugees rather than the large historical events?

Yes. I not only wanted to tell the story of the refugees, but of a poor refugee woman. Those are the stories that are completely whitewashed. And you only hear about them as numbers, because when I was doing research, I did not even find a lot of anecdotes other than [the number] “2.5 million refugees.” But we all tell stories. I mean, you may not have anything, but you still have a history. My grandmother was both a writer and an activist for refugee work. She had this complete empathy for the east and for the Bengali refugees. I was reading through her short stories, and I found her focusing on this class of people in her short stories. And what really stuck with me was that all her stories ended in tragic circumstances for the characters. And I somehow wanted to reimagine the life of such people, because those were tragic times. But there still were some redeeming features. And there could be hope if hope could be found. That was where I was going.

In the book, in addition to showing us the tragedies and later the triumphs of the refugees, you also show us there was a fundamental class division that was still very hard to overcome in some of the characters, mainly Manas’ mother, Mrinmoyee. What was the impact of those class divisions on the refugees, and how common would it have been for people to marry not only outside of their class but with a refugee?

Yes, the class differences were quite sharp and entrenched. They still continue to be that way, at a lesser stage, of course. But at the time the novel is set, the class differences were entrenched in the minds of a person like Manas’ mother: she is kind of cloistered in her environment, she hasn’t had a chance to [get] much education. So, she’s really living within the parameters of her understanding of her world. And then suddenly there is this outside force coming in, which she does not know how to deal with. So, she is only behaving the way she was to work, you know, her experience and her overview of the world. But other than that, this kind of relationship [between an upper-class man and a refugee woman] would have been quite rare, but not impossible. Bengal was the site of a renaissance in India that saw a lot of awakening and social reforms in the 19th and 20th centuries. And so Manas is an outcome, a product, of that kind of thinking.

Aside from the historical aspect, which I found deeply compelling, one of the things that struck me the most was the wonderful sense of place you create in the novel, from the light, the smells, the colours, the flavours – there are a lot of sweets shared throughout – it’s so evocative. How important was it for you to create this sense of place?

Extremely important; as important as the characters themselves. The city becomes a character. [Calcutta] is suddenly seeing this influx of refugees and there is a lot of tension between the locals and the newcomers. And then, how does the city respond? It also has its limits, its physical limits. So, for the reader to go back in time, you have to create that sense of what that time was like. And for that, the place is an excellent marker. People who are from Calcutta have told me that it kind of made them nostalgic for a Calcutta of yesteryear which is kind of receding now. It’s still there, amazingly – the city is such that it still retains some of its ancient, very old characteristics. But with modernization, with new things coming, with all the capitalist trappings of today, the character of the city is changing. So, I was glad that sense of place came out. That was very important to me.

Victory Colony, 1950, was published in August 2020 by Yoda Press.

French Editor - Born in Venezuela, Andreina Romero is a freelance writer with New Canadian Media. Prior to writing for New Canadian Media, Andreina was a bilingual contributor at The Source Newspaper, also known in French as La Source, an intercultural newspaper in Vancouver. She is also the creator and host of the podcast Girls Talk About Music and Wigs and Candles which explore music and period films from a uniquely female and Latin American lens. In 2020, Romero also co-founded Identity Pages, a youth writing mentorship program.