Nelofer Ahmadi is a 30-year Canadian Iranian woman whose parents came from Iran before she was born. So while Ahmadi’s parents practise their customs and culture, Ahmadi has adapted to life in Canada, adopting Canadian ways and that has led to conflicts with her parents.

Ahmadi is not her real name as she asked to use a pseudonym for fear of the impact this story would have on her career, studies, and family relationships.

A clash between first and second generations in Canada is a phenomenon that can cause problems within families. The first generation — parents who were born elsewhere and moved to Canada – tend to keep their original cultures, languages, and behaviours, and try to impose them on their children. The second generation, on the other hand, – those born in Canada with at least one parent born outside the country — tend to adapt to, and sometimes embrace, Canadian culture.

“My family came from a more conservative culture,”Ahmadi told New Canadian Media. “As a result, they applied traditional views on a variety of topics, such as friends, relationships, mental health, and proper social etiquette.”

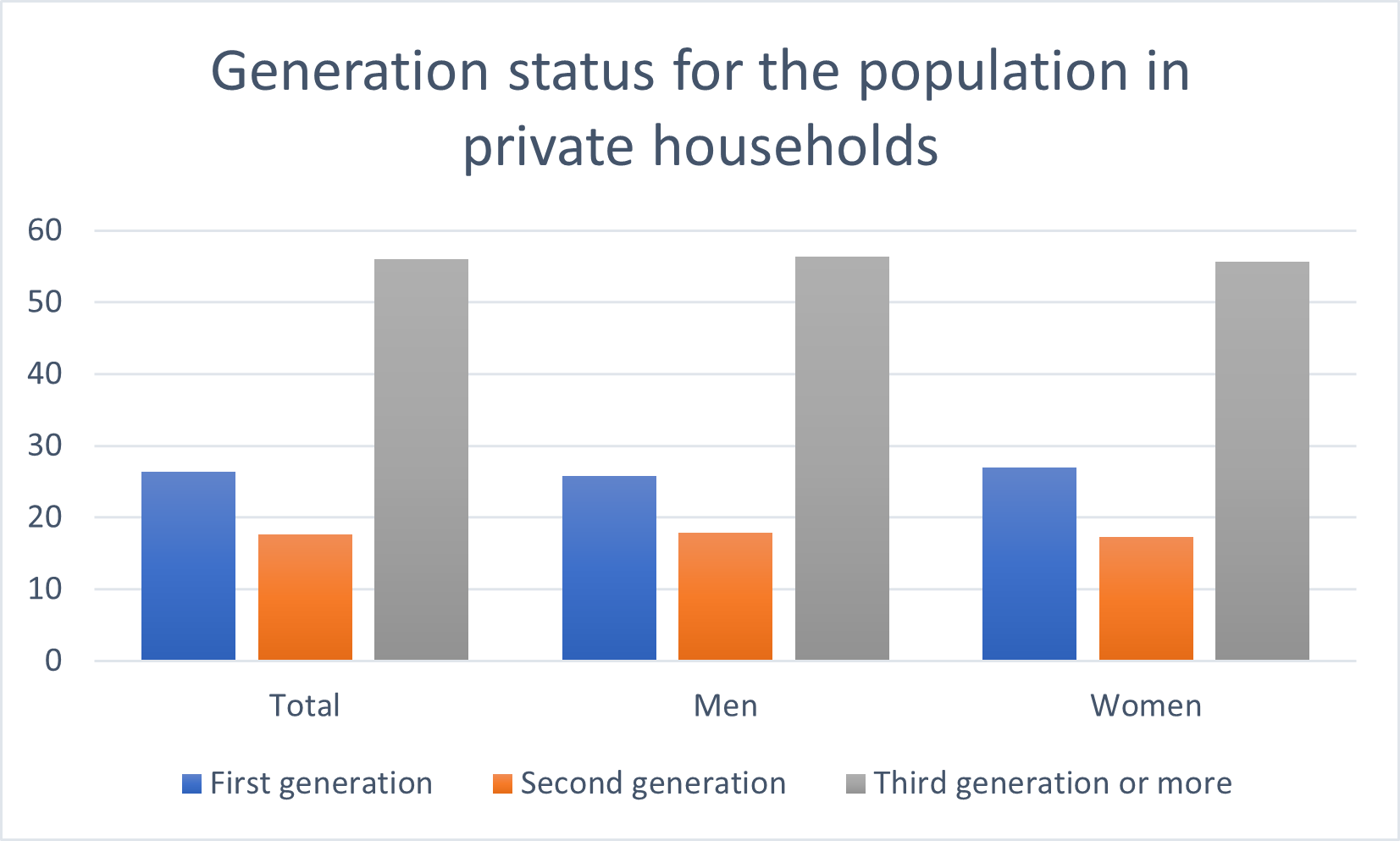

According to the latest data on immigration from Statistics Canada, 56 per cent of the population are third-generation Canadians — both parents were born in Canada — followed closely by first-generation (newcomers) at 26.4 per cent.

Second-generation Canadians are the smallest group with a 17.6 per cent population size.

From one conflict to another

Many of the people immigrating to Canada do so to escape conflict in their home country. In Canada, they now face family conflict.

Experts in early childhood education call this phenomenon the acculturation gap. It’s a process that begins when immigrant parents enter the new country and centres around changes in language, behaviour, attitudes and values, according to the Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development.

“Children become involved in the new culture relatively quickly, particularly if they attend school, but their parents may never acquire sufficient comfort with the new language and culture to become socially integrated into their new country,” write University of Illinois at Chicago’s Dina Birman and Meredith Poff. “In addition, immigrant children may have few opportunities to participate in and learn about their heritage culture.

“As a result, immigrant parents and children increasingly live in different cultural worlds.”

Immigrant parents may try to teach their children about their culture and how to preserve it. But their children don’t have the home country in their hearts or minds, and Canada is all they may know. As a result, they quickly adopt the cultures and norms of their adopted country. And this often puts children stuck between the two cultures and feeling like outcasts in both.

“I felt I was in two worlds. I wanted to please my parents while trying to fit in here,” Ahmadi said. “I still struggle with this. I felt my transition into adulthood was delayed compared to my peers because it took me longer to learn that my happiness is what matters and not that of my parents.”

Ahmadi is not alone. Her friends whose parents came from other countries face similar conflicts with their parents.

Trifa Saeed is a registered therapeutic counsellor in British Columbia. She says that sometimes conflict happens between immigrant parents and their children when the children try to develop their own personalities and follow their own paths. Parents, on the other hand, want to teach their children their culture and want the children to preserve that culture for subsequent generations.

“It is a kind of war as the parents want to keep their values alive throughout the generations and they demand that their progenies act, think and behave [like they did.]”

NCM reached out to several parents regarding this issue but all were reluctant to speak on the issue as they worried it would affect their relationships with their children and they did not want their relatives in their home countries to know about their problems.

But some mentioned feeling isolated with their children seeing them as strangers at home. They are also sometimes mocked for their English accent and clothing.

Saeed has been counselling immigrant parents for a number of years. She says the clash between generations from one geographical background is not necessarily the same as the clash among those from other regions.

“For example, for some from Middle East countries, the cultural clash is harder for girls,” Saeed said. “Girls should follow family traditions and rules or face punishment.

“Females are responsible for the family’s honour. Unfortunately, in the past and now in many Western countries including Canada many women have been killed or sent back home forcefully due to cultural clashes”.

How do generations come together?

Despite Ahmadi’s conflicts with her parents over the years, she suggests that everyone, irrespective of culture, should place themselves first in their life as much as they care for others and their family.

“Family is very important and we all need a social support system,” Ahmadi said. “In this society, family and connection are being discouraged.”

Saeed suggests that good communication in a non-judgmental way is key for parents to be able to impact and guide their children. And both parents and children should be willing to balance the culture of their home country with that of Canada, and be open to adopting some new rituals and ethics in their lives in the new country.

___________________________________________

Additional data reporting and graphic by Kaitlyn Smith

Diary Marif is an Iraqi Kurdish journalist based in Vancouver, Canada. His writing has appeared in the Awene weekly, Livin, and on KNNC TV as a documentary researcher by the name Diary Khalid. Diary earned a master's degree in History from Pune University, in India, in 2013. He moved to Vancouver in 2017, where he has been focusing on nonfiction writing. He can be found on Twitter: @diary_khalid.