Dynamic, committed, and growing – these are a few words that sum up the Francophone community of Yukon, according to Isabelle Salesse, Executive Director of the Francophone Association of Yukon (Association Franco-Yukonnaise (AFY)). Although a linguistic minority, Yukon’s Francophone community is more lively than ever. According to a Statistics Canada census, Yukon is the third most bilingual territory with 14 percent of the population speaking French and English.

Between 2001 and 2016, people whose mother language is French increased from 3.33 percent to 4.8 percent. And according to Salesse, future statistics will continue to show an increase. “If you come to Yukon, you will be impressed by the number of people who speak French, in the street, in the grocery store… every day I discover new Francophones,” she says.

From the Gold Rush to linguistic demands

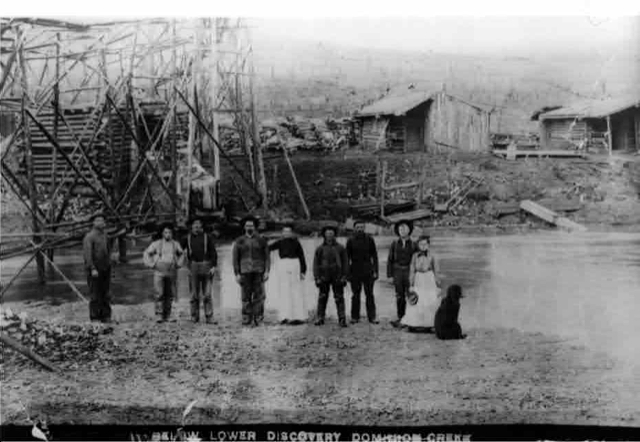

According to Yann Herry, president of the Francophone Historical Society of Yukon and former president of the AFY, the first Francophones arrived in the territory in 1833, attracted by the fur trade. Starting in 1896, the Klondike Gold Rush became the main incentive to move, and Francophones from all over decided to try their luck in Yukon.

The historian estimates that at that time, more than 4,000 Canadians spoke French, which was half of the Canadian population established in the territory. During this golden age of the Yukon’s Francophonie, a number of public services were created in French. “When the miners came down to Dawson, they could easily get services in French because the gold commissioner and many of the court judges spoke French,” explains Mr. Herry. Health services, education and even cultural circles were available in French.

However, by 1911, the Francophone population had declined significantly. Major political and economic changes, including the replacement of manual labour by mechanized dredges, forced many Francophones to leave the territory. The few who remained were quickly assimilated into the English-speaking majority.

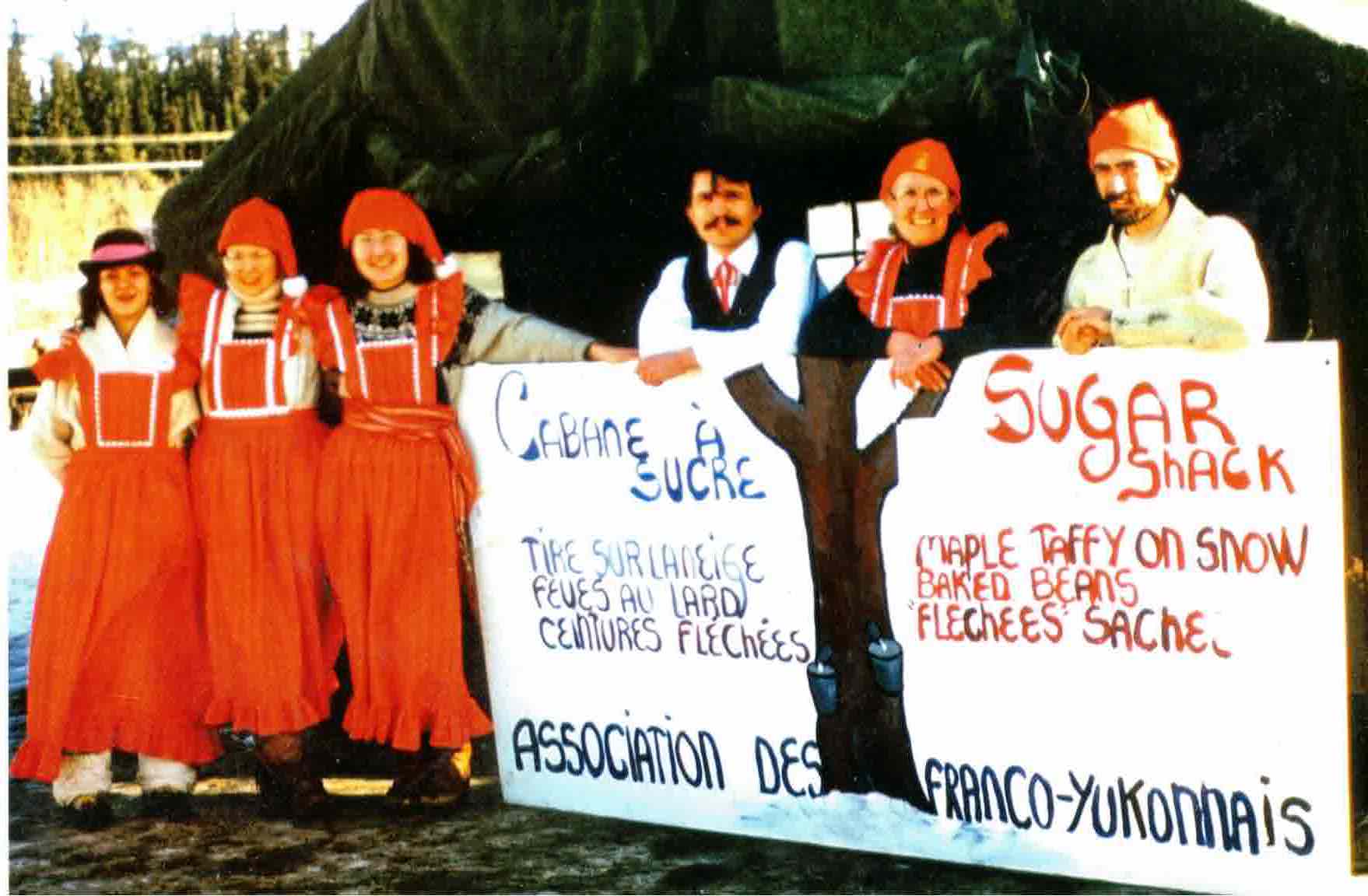

But in the 1970s, the Yukon’s Francophone community experienced a revival. As the Official Languages Act came into force and the country experienced a national search for its Francophone identity, Yukon’s Francophones began to demand public services and institutions in French. In 1982, a handful of determined volunteers decided to found the AFY, thus paving the way to living in French in Yukon.

Growing French education

Unlike in most English-speaking provinces, French as a first language education is doing relatively well in Yukon, according to Jean-Sébastien Blais, president of the Yukon Francophone School Board (Commission Scolaire Francophone du Yukon (CSFY)). He says that section 23 of the Canadian Constitution, which guarantees the right to minority language education, is respected in the territory.

But to get there, the CSFY had to fight. In 2009, the organization took legal action against the Yukon Department of Education to gain full school governance. Under a 2020 agreement with the provincial government, the CSFY was granted the authority over admissions and a funding formula. “We are lucky in Yukon.” says the president of the CSFY. “We have excellent funding that allows us to have an education and extracurricular activities that support our students in their development.”

Most importantly, the agreement allowed the CSFY to address a major issue: the lack of infrastructure. Prior to 2020, secondary school students were forced to share school facilities with elementary students, which led many parents to unenroll their children. Today, the CSFY has opened a secondary school, the CSSS Mercier. In just over two years, the number of students grew from 86 to 122. “The Mercier school has a capacity of 150 students, so we are already wondering if we are not going to experience the same situation we had before 2020,” notes Mr. Blais, who is considering opening a new school.

As for French immersion, it is also growing. According to Statistics Canada, since 2001, the number of students enrolled in French immersion has increased by 248 percent. “There is a real craze for French immersion,” says Isabelle Salesse. “Here, French is very accepted and people are interested in learning the language.”

Challenges ahead

Despite the progress, the Francophone community of Yukon still has a long way to go. Ms. Salesse, the AFY director, believes that there is still a lot of progress to be made, especially regarding the justice system and the services for seniors, which must be further developed in French.

In addition, the community is facing a critical shortage of qualified Francophone workers. This is particularly the case for the association Les Essentielles, an organization working to represent the interests of women in Yukon. “We don’t have the human resources to meet the needs and the projects that could be implemented,” says Laurence Rivard, director of the association. “There are certain opportunities that we have to pass up because we would not be able to deliver the services.”

This situation has been worsened by the pandemic as the majority of the staff is composed of young “pvtistes,” immigrants from European nations. The term “pvtistes” refers to people who immigrate to Canada on a working-holiday visa (“permis vacances travail” in French).

Moreover, the recruitment of qualified personnel is becoming increasingly expensive. Salaries must be able to compensate for the cost of living in Yukon, while real estate prices continue to rise as well. She also explains that the workforce shortages are a consequence of the lack of access to post-secondary education opportunities in Yukon. As a matter of fact, it was only in 2020 that the very first university opened its doors in the territory. This situation forces Francophone graduates to leave Yukon to continue their studies in French.

According to Isabelle Slesse, hiring French-speaking staff is also difficult in the health, French immersion, and early childhood education sectors. In 2008, the “Garderie du Petit Cheval Blanc” and the AFY even went to Belgium and France to recruit qualified personnel during the Destination Canada mobility forum. This event, organized annually by the federal government, aims to put Canadian employers in touch with qualified French-speaking candidates.

Aware of this labour shortage, the Yukon Government, in partnership with Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC), has implemented the Yukon Nominee Program (YNP). Since its launch in 2007, the program has helped nearly 400 employers to meet their needs in recruitment. Among the candidates selected by the YNP, the vast majority were from France.

Despite these adversities, the Yukon Francophone community has made surprising progress within only 40 years. And according to Laurence Rivard, the progress made could serve as a lever for the Yukon’s Indigenous communities, who also want to make their rights and demands heard, particularly with regard to school management.

Daphné Dossios

Daphné started her journalism journey in Switzerland, after graduating with a Bachelor in Political Science. She then decided to immigrate to Vancouver – unceded territories of the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh Nations. Before contributing to the New Canadian Media, Daphné was a frequent writer for the bilingual newspaper The/La Source. An avid learner, Daphné was recently selected for a Master's degree in Journalism at the University of British Columbia which she will begin in September 2022. Daphné is particularly interested in social justice stories, especially regarding refugees, and Indigenous and 2LGBTQ+ communities.

[…] Francophone minority communities: the special case of Yukon New Canadian Media – English speaking from Francophone minority communities: the special case of Yukon New Canadian Media – visit this link please – Read More by “englishspeaking” – Google News […]